Fringe Festival's second weekend: Vexed and vexatious families and frayed bonds

Many years ago, reviewing theater for the Flint Journal, for several summers I got to zip over to Stratford, Ontario, during opening week of its Shakespeare Festival. By the early '70s, the event had spread its wings to glide through more non-Shakespeare productions. It eventually dropped "Shakespeare" from its name, while continuing to specialize in the Bard of Avon's plays, most of them presented on its sturdy thrust stage. No artfully framed proscenium-arch peep-show presentations for the Stratford Festival! Speedy aisle entrances and exits and an emphasis on main-action three-dimensionality were embedded in the style.

Memorable in this repertoire among the guest stars was the appearance of Peter Ustinov in the title role of "King Lear." An actor of considerable range and subtlety, Ustinov had a genius for comedy. So his casting in the leading role of Shakespeare's most searing tragedy stirred both eagerness and anxiety.

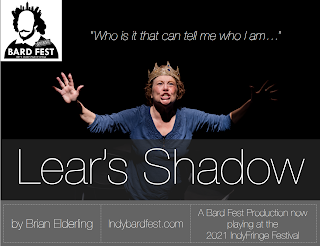

The role is regarded as "unactable" with admiring despair by critics alluded to in "Lear's

Shadow," the Bard Fest production at the current Indianapolis Theatre Fringe Festival. Brian Elerding's play is both about "Lear" and through "Lear" in applying contemporary family tension, a tragic accident, and behind-the-scenes troupe troubles to the original. I'll never forget Ustinov's entrance from a darkened upstage, the intermittent glow from a cigar clamped in his teeth leading the way, moments before a word was spoken. Lear's resolve to divide his kingdom by testing his three daughters' expressions of devotion was foreshadowed in that fierce glow.

The ancient king was presented as unshakable partly through the production's way of contrasting Ustinov's entrance to the promise of helter-skelter thrust-stage presentation. People who, without justification, seem to know their own minds too well can be inadvertent clowns, as Lear's Fool helpfully establishes in Shakespeare's play. Ustinov's Lear and his Fool were brothers under the skin. His Lear could rage on the heath as well as any, but what a shift in understanding the play was required to see Ustinov make a qualified success of it! The leading role proved actable after all. The ridiculousness of the king dug deep.

Elerding's Jackie, with Nan Macy playing the role originally designed for a man, seems irascibly self-possessed as the major force behind a small, serious company. But the character's entrance is distracted, with a mysterious air of anticipation and irritation. It turns out her standards are as inflexible as Lear's, whose persona she takes on at a trusted colleague's invitation as she waits for a rehearsal to begin. "Where's Janine?" she keeps asking, and we believe in the perceived necessity of Janine's appearance even as we know next to nothing about her.

But Jackie is damaged in judgment and her wonted capability, a fact drawn to her attention firmly and at first tactfully by that trusted colleague, Stephen (Mark Hartzburg). There is no touch of humor here. We learn why Janine will not be showing up. The appearance of daughter Rachel (Afton Shepard) is simply delayed until the conflict between Jackie and Stephen reaches fever pitch. A resolution is wrenched from their conflict, which shadows the opposition of the mad Lear to the entire world. The secondary plot is wisely and explicitly discarded: there is no place for Gloucester or his scenery-chewing sons, Edgar and Edmond, in this small-group therapy.

Therapeutic immersion in Shakespeare's play proceeds for Jackie and Stephen. The two actors conveying huge chunks of the original work well together while dealing creatively with the present-day people they are supposed to be. Glenn Dobbs directs them with insight into the play's difficulties. Each is obliged to "tear a passion to tatters," to quote Hamlet's famous warning to the Player King, and so they do.

The playwright deals too obliquely with the parallels between the addled king and his disfavored daughter Cordelia on the one hand and Jackie and Rachel on the other. Nonetheless, Rachel is touchingly worked into the overwhelming pathos of the tragedy's ending, with Stephen incidentally getting help overcoming a persistent deficit in his acting: he has been unable to cry onstage. In a tightly packed hour, Elerding has scrutinized the politics of theater and family life while doting on Shakespeare. It's the kind of fantasy many actors and directors might get behind; in "Lear's Shadow," audiences can share in the spellbinding encounter.

Stubbornness crossing over into senility, much more lightly treated, also concerns Garret Matthews in "Driving Kenneth and Betsy Ross." Presented on the modest Oasis stage at the Murat, the show sets three actors in a similarly modest mockup of a car seen from the front as a Southern car trip of 2010 is evoked. Driver Colin, the title couple's son (Thom Johnson), is a middle-aged historian of the civil rights movement who has long been at ideological loggerheads with his father, Kenneth. To their conflict, wife and mother (Wendy Brown), carrying the iconic name of Betsy Ross, provides both insight and conversational distractions. Both parents seem infirm, though Betsy sees her husband's drawn-out loss of physical and mental abilities more steadily, and he acknowledges his weaknesses hedgingly.

The playwright makes use of a couple of long parental bathroom trips to permit dialogue between Colin and each one. Some chores of exposition are thus dispatched. The work feels overreliant on its simplicity of structure, with maybe too little heightening of the long-running lack of rapport between father and son. Kenneth's prejudices are stoutly expressed but mild compared to the explicit racism we have all recently become familiar with. Any nastiness is expurgated, except for the old man's gross focus on his digestive tract.

Matthews is clearly wanting to emphasize the family bond and to sound the theme, wedded to the old song "Sentimental Journey," that family ties endure and can be secured with nostalgic warmth during a rare automobile trip together. The cast plays comfortably with their roles, but "Driving Kenneth and Betsy Ross" leaves lots of room unoccupied to explore how white families process internal conflict over racial attitudes — even given the hour limit of Fringe shows.

I was further out of my comfort zone in Casey Ross' brilliantly written "Copyright/Safe," an

intense fantasy involving the dilemma of four comic-book characters after their creator has died. Their identities are totally manufactured, yet each one is burdened with marketable self-esteem. How much does that resemble true individuality, and how will they face the end? And what remains in the narrative of their valuable and renewable identities, primed for combat and a connection with fandom so intense that it has generated a fan-fiction subgenre?

As The Mask, Taylor Cox masters such a role. You might call it fawn-fiction, dependent on faithful imitation of storylines and set behaviors created by the genre's geniuses. If you're a fan, you buy into the fates of the characters and try to contribute to them. The Mask is comically integral to the assertive struggles of Badger (Dave Pelsue), Eyepatch (Zach Stonerock), and Creature (Doug Powers). All are authentically costumed with signature specificity by the play's multifaceted author. The competitiveness runs in certain prescribed channels, against which the characters struggle for assurance that the creator's death is not also their own.

Pelsue takes a break from Badger's thundering rants to sing several original songs, which lay stress on the fate of creatures who are as hedged in by their vivid stock personas as today's Republican candidates are by their primary voters. The final song addresses the open question of endings by defining them as "continuation forever." It's not the same as immortality, but a kind of death-in-life ruled by market forces and fields of action too stipulated to be redirected. Somehow the vitality has to be resupplied by new creators who may be put into place by corporate takeovers. "Copyright/Safe" is a blisteringly funny parody about our illusions of freedom. Comic-book culture is the cleverly assembled vehicle for carrying our imaginations to someplace less bleak than continuation forever.

In the same venue, "Being Black: The Play — the Life" puts together post-George-Floyd vignettes of African-American life in conflict with itself as well as with the white mainstream. Tijideen Rowley directs the ensemble cast of eight. Vernon A. Williams' fast-paced script has the persistent exuberance and jeremiads of hip-hop, with some of the richness of imagery dating back beyond the scintillating poetry of Melvin B. Tolson to the black tradition of storytelling that testifies and amuses at the same time.

Some of the vignettes are sobering indictments of white supremacy; others tackle illusions that remain embedded in that relationship as well as illusions that divide the black community. A job applicant gets advice from a company man to

temporarily alter her officially questionable hairstyle in order to land

a job that will increase black representation on the company's staff.

It's a vigorous battle in which the applicant finally gets the upper

hand over the recommendation that she trim her sails for the time

being.

A popular deejay runs down the pantheon of black music, demonstrating the integral role his job plays as protector of a vast legacy. But he also advises the sanctified critics of the secular love songs he broadcasts: "Stop playing church, y'all!" That's among the energetic monologues, the most riveting being Monica Cantrell's explanation of why even well-off blacks don't go in for adventures like skydiving and whitewater rafting. They live an adventure every day, she explains fervently, even though it is not a matter of choice: the adventure of surviving as black in America while jogging or sleeping or playing with a toy gun in a public park.

There are lots of powerful words delivered in this show, often at too fast a pace. But early on it was a wordless gesture that moved me most: When Shirley tries to restrain her husband Cliff, aroused by the latest police outrage, from participating in a possibly dangerous demonstration, she reminds him verbally of the status in life he has worked so hard to attain.

But a well-meant wifely lecture can't say everything. So then she puts a hand, palm up, under his chin and gently lifts his head.

Comments

Post a Comment