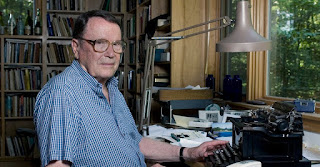

The cymbal crash at the end: A meditation on last lines in poetry (in memoriam Richard Wilbur)

There is no good ending admits fade-out.

—Geoffrey Hill, "Improvisations for Jimi Hendrix"

|

| Richard Wilbur: The image of his poems' cymbal-crash endings stayed with me. |

When I first encountered Wilbur's work, I was a sophomore English major at K College. Something that she said about Wilbur's poetry — the best of which was fresh and modern in 1964 — has stayed with me. "I like the way his poems end with sort of a cymbal crash," she said.

I don't remember which Wilbur poems she cited, but I'm sure we had some of the same ones in mind. "Advice to a Prophet," for example, with its formal stanzas warning a generic prophet against an exclusively human emphasis in the doomsday scenarios that were in the air then as now:

Ask us, ask us whether with the worldless rose

Our hearts shall fail us; come demanding

Whether there shall be lofty or long standing

When the bronze annals of the oak-tree close.

CH-issshhhh!

Or "Still, Citizen Sparrow," painting at first a contrast between the common life of the sparrow and the predatory one of the vulture, before moving to Noah's lofty perspective at the Ark's helm above the flood:

...Try rather to feel

How high and weary it was, on the waters where

He rocked his only world, and everyone's.

Forgive the hero, you who would have died

Gladly with all you knew; he rode that tide

To Ararat; all men are Noah's sons.

Chissssh!

Or what the soul says to the waking body in contemplation of clean laundry on clotheslines in "Love Calls Us to the Things of This World":

Let there be clean linen for the backs of thieves;

Let lovers go fresh and sweet to be undone,

And the heaviest nuns walk in a pure floating

Of dark habits,

keeping their difficult balance.

Chissssh!

The cymbal-crash resonance of poetic endings is no easy test of a poem's worth, however. And its perception by a reader may be too seductive. As a teen-ager, I probably overestimated two overanthologized poems because of how they ended, conclusions that noisily turned the key in the locks of two brief lyrics: E.E. Cummings' "Buffalo Bill's" and E.A. Robinson's "Richard Cory." The legendary showman and sharpshooter in Cummings' poem has passed on, so that the poet asks: ...and what I want to know is / how do you like your blueeyed boy / Mister Death" and Robinson's debonair envied townsman who "one calm summer night / Went home and put a bullet through his head." I loved the airtight conclusiveness of those lyrics.

When we are first fired up by poetry, we may resist scrutinizing such definitive endings as gimmickry. Later on, we assemble a repertoire of personal cymbal-crashes in last lines that seem better earned. William Butler Yeats was a master of them; no one could elude fade-outs better, as we know from the oft-quoted lines ending "The Second Coming," "Prayer for My Daughter," and "Sailing to Byzantium."

When a poet uses a refrain, he potentially dissipates cymbal-crash energy across the whole poem. That threatens the specialness of the final iteration.Yeats finds a way of making the last time special in "John Kinsella's Lament for Mrs. Mary Moore," because he contrasts the joys of the fallen world with prelapsarian grace in Eden, coming out in favor of the former. The last four lines: "No quarrels over ha'pence there / They pluck the trees for bread. / What shall I do for pretty girls / Now my old bawd is dead?"*

Chissssh!

In older poetry, making a big deal over the last line fitted into the smoother rhetoric the Romantics developed. Today you don't get the kind of predawn view of any metropolis available to William Wordsworth of London in 1802. After sustained exaltation, the sonnet "Composed upon Westminster Bridge" ends, "And all that mighty heart is lying still!" The poem has already been stuffed with wonder at the quiet city, but the last line tops everything. It does so partly though its sound: All monosyllables except for two words with the open assonance of "mighty" and "lying."

Since the clash of cymbals is sound, the sound of lines with such clashes is not irrelevant. Another such is the close of Tennyson's "Ulysses." Encouraging himself and his crew to undertake a final voyage, Ulysses ends his pep talk with "...that which we are, we are, — / One equal temper of heroic hearts, / Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will / To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield."

You can't resist that — you're ready to sail!

Nothing but monosyllables in the last two lines, capped by those thundering infinitives. You can almost hear a cymbal crash on each verb, not merely a strong accent.

As you come to admire last lines, you realize that a lyric poet is always fearful of fade-out, in a career as well as in a poem. This has resulted in great poems with cymbal crashes that feel a bit like tags. There is didacticism in the ending of Keats' "Ode on a Grecian Urn" and Robert Frost's "Directive," two extravagantly admired examples of those poets' mastery. The detail in each is exquisite, but we can be made uneasy by the "directives" ending each of them, not just Frost's "Drink and be whole again beyond confusion," but also Keats' "Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

Only each poet's skill in building toward them seems to justify such sententious endings. You can feel other poets gauging their endings carefully, resisting tying a fancy bow on their gift. The famous conclusion of Wallace Stevens' "Sunday Morning" is a patterned cymbal crash in diminuendo. He could be more direct about it elsewhere, but indirection was his metier, and the gaudiness of his imagery seems designed not to put too much weight on a poem's conclusion. A notable exception is "Disillusionment of Ten O'Clock," where muted, glum color imagery gives way at the end to

Only, here and there, an old sailor,

Drunk and asleep in his boots,

Catches tigers

In red weather.

Cymbal crash! And also in the bleak lyric "The Snow Man." It's a cold cymbal crash, and it can make us uneasy about the poem as well as about Stevens' uncustomary explicitness. Evoking the feeling of a January wind near woods "That is blowing in the same bare place / For the listener, who listens in the snow, / And, nothing himself, beholds / Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is." A cymbal crash of nothingness.

Always something of a sport, Stevens felt the hazard of majestic cymbals at the end; stuttering inconclusively, he ends "The Man on the Dump" with this: "Where was it one first heard of the truth? The the."

|

| John Ashbery (1927-2017) |

...We come back to ourselves

Through the rubbish of cloud and tree-spattered pavement.

These days stand like vapor under the trees.

Not a Wilburian cymbal crash, but still....

Here's an odder one, and I can't account for in its effect on me. A distant castle, sprung up out of nowhere like so many things in Ashbery poems, "...weighs its shadow ever heavier on the mirroring / Surface of the river, surrounding the little boat with three figures in it." I have no idea why I find the final image so moving; maybe it's because humanity is somewhat intrusive and threatening throughout much of "Voyage in the Blue,"* and at the end is comfortingly seen from a distant perspective.

|

| Geoffrey Hill (1932-2016) |

It's also a cymbal crash, but perhaps Jarrell's complaint reflects the fact that one reader's splash of triumphant percussion may be another's banality indicating that too much of a poem's inspiration depends on the conclusion it's moving toward. This is part and parcel of lyric poetry's anxiety about death. A clear vision may be welcome, but how does it stand beside cloudier poetic visions?

My epigraph for this essay comes from the response of one relatively long-lived artist to a short-lived one. "Improvisations for Jimi Hendrix,"* which uses as its theme lyrics to "The Wind Cries Mary": Geoffrey Hill's style is both wide-ranging and knotty, as if the way to proceed is always a problem of focus, a responsibility that must be confronted. Yet, suddenly, here he is on a high plain of forthrightness. The poem ends:

Somewhere the slave is master of his desires

And lords it in great music

And the children dance

Cymbal clash of grace and clarity from an often deliberately graceless poet? Or a burst of sentimentality, special pleading, even a bid for applause? As in music, concluding cymbals can carry either message, or both.

With Richard Wilbur's measured, elegant muse, the memorable endings almost always have the authentic ring. Thanks, Barbara, wherever you are now, for the insight.

[*In some editions, the two lines before the final refrain in "John Kinsella..." are slightly different. I was unable to find online texts of Ashbery's "The Gazing Grain" and "Voyage in the Blue" and Hill's "Improvisations for Jimi Hendrix." They may be found in the volumes "Houseboat Days," "Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror," and "Without Title," respectively.]

Comments

Post a Comment