In-the-moment done deals: The joy of an Indy Actors' Playground cold reading

For years, two critiques of theater by famous novelists have stuck in my craw, and I can't say that either one is easy to dismiss. I can minimize them, though. So I was happy to be confirmed in my belief in the viability of stage drama by the richness of Indy Actors' Playground's January "cold reading" last night. Attempts by John Updike and Martin Amis to disparage theater rest on two different foundations, both of them worth considering, yet faulty.

Lou Harry and Paul Hansen, co-masters of these long-running revels, once a year depart from the format of a reading chosen by one actor, who selects a cast of fellow readers; then the ad hoc troupe comes to the Playground with minimal to no rehearsal. In IAP's "cold cold reading," actors are invited to participate by the founders and handed an envelope with their parts marked. It's showtime. Until a given signal to begin, they don't know what's inside.

Monday's show, an amusing but overstuffed travesty of Shakespeare's "Much Ado About Nothing," with an overlay of satire aimed at British pop culture of the late 20th century, required a cast that spilled over the sides of Indy Reads Books' cozy stage. The actors had me believing in an inherently incredible spoof. Through them, I knew these people, even they were the most transparent of caricatures.

A significant part of the entertainment was the opportunity to be awed by how thoroughly trained actors can puff life into characters they've just met. Believable impersonations, instantaneously realized, resulted. An actor's imagination and his/her ability to convert its work into a simulacrum of reality on the spot partakes of the miraculous in my admittedly skeptical view of miracles.

Of course, there's usually years of training involved. As with most advanced skills, there was surely in everyone onstage an early knack for getting it right, which they built upon. And there's current involvement in theater to keep the requisite chops fresh and applicable to new teams and new roles, not to mention the stress of door-opening auditions. As among classical musicians, there are variations in the poise and accuracy of sight reading among artists. Usually adequate rehearsal (with coaching and direction, where necessary) eventually puts them on the same level playing field before the public.

But I'm continually struck by the snap-crackle-pop of impersonation. The great drama critic Max Beerbohm always referred to actors as "mimes," a word we too exclusively apply to pantomime, the wordless artistry of Marcel Marceau and his descendants. But "mime" also draws upon the origins of the word in ancient Greek and Roman shows of simple, often ridiculous imitation. There's a comic aspect to pretending to be another person, a kind of parlor trickery, even if the vehicle is tragedy.

This potentially uncomfortable basis of the art provides a way in for the scorn of Amis and Updike. The American author died in 2009 after a staggeringly prolific career as an honored man of letters. Somewhere he says that theater rests on the weak basis of making scrupulously prepared utterances and actions seem to be spontaneous.

The studied aspect of theater erected an obstacle for Updike, even though he wrote a sort of playable play about the only president to come from the author's home state of Pennsylvania, James Buchanan. To Updike, theater's artificiality was insurmountable and false to life. What characters do and say in a novel or short story takes place in a perpetual present; readers and re-readers make it happen as they proceed through the text. Dialogue and action in a staged play happen within a span of time — a span that's replicated and similarly filled more than once, for audiences, by people assigned to represent events and utterances that pretend to be unpracticed. How can that be anything like life?

The parlor-trick aspect of acting also bothers the Englishman Amis, but mainly as a way to cast into suspicion the whole theatrical legacy. Amis heaps disdain upon a playwright's collaboration with a host of others; the playwright necessarily distances himself from the lives he purports to represent. There are too many others involved. Amis seems to be asking, Where's the artistry in that? "All he has done is finished the dialogue; and, as any novelist knows, compared to the other exertions of fiction the demands of dialogue are negligible."

The essay in which this appears seconds Vladimir Nabokov's own dislike of theater, despite the book under review being a volume of the Russian-American writer's early plays. Amis makes an exception for Shakespeare, but for him it's an exception that proves a dismal rule. In a typically vivid comparison, Amis explains: "The fact that Shakespeare should have been, of all things, a dramatist is one of the great cosmic jokes of all time — as if Mozart had spent his entire career as second wash-board or string-twanger in some Salzburg skiffle troupe."

It's an amusing but nonsensical analogy, really. But novelists, who are apt to exaggerate the heroic loneliness writing fiction, may be peculiarly susceptible to it. They may play well with others, but working well together is beyond the pale. In his Paris Review interview, Ernest Hemingway said truly that "the most essential gift for a good writer is a built-in shock-proof shit detector," but its mechanics tend to break down when applied to one's own work, as his did. Novels aren't workshopped or devised, and more's the pity, perhaps. (Hemingway came up with a provocative, short closet drama about the Crucifixion, "Today Is Friday.")

Another prolific English novelist, Anthony Burgess, suggests in "Nothing Like the Sun" that Shakespeare yearned to be a lyric poet, but resorted to the theater as a fallback career choice. Hmmm....did we really need more of "The Phoenix and the Turtle" or "The Rape of Lucrece"?

So there you have it: Drama is either a slender reed, always propped up, crafted by committee, and on the brink of wilting and withering in the garden of art (Amis) or it's a scam, since everyone knows that the mimicry is basically contrived deception, at too far a remove from how people actually talk and act (Updike).

To me, though readers' theater is not the ultimate expression of its art form, it may indicate how lifelike working unprepared from a script can be. It largely sidesteps the objections of Amis and Updike. Except for the interaction happening immediately before us, it reduces collaboration to a minimum. It brings to the fore the sprightliness of the text itself, thus coming close to the immediacy of spoken dialogue in real life. Nonetheless, while the perspective of good readers' theater may win this argument, it remains rudimentary to the greater glory of full-fledged theater.

Novelists, I love you, but please tend to your knitting. I'll still often want to drape myself in the finery of theater, in its blend of natural and artificial fabric.

Lou Harry and Paul Hansen, co-masters of these long-running revels, once a year depart from the format of a reading chosen by one actor, who selects a cast of fellow readers; then the ad hoc troupe comes to the Playground with minimal to no rehearsal. In IAP's "cold cold reading," actors are invited to participate by the founders and handed an envelope with their parts marked. It's showtime. Until a given signal to begin, they don't know what's inside.

Monday's show, an amusing but overstuffed travesty of Shakespeare's "Much Ado About Nothing," with an overlay of satire aimed at British pop culture of the late 20th century, required a cast that spilled over the sides of Indy Reads Books' cozy stage. The actors had me believing in an inherently incredible spoof. Through them, I knew these people, even they were the most transparent of caricatures.

A significant part of the entertainment was the opportunity to be awed by how thoroughly trained actors can puff life into characters they've just met. Believable impersonations, instantaneously realized, resulted. An actor's imagination and his/her ability to convert its work into a simulacrum of reality on the spot partakes of the miraculous in my admittedly skeptical view of miracles.

|

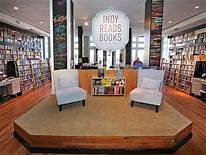

| Venue for a miracle: The bookstore stage for Indy Actors' Playground |

But I'm continually struck by the snap-crackle-pop of impersonation. The great drama critic Max Beerbohm always referred to actors as "mimes," a word we too exclusively apply to pantomime, the wordless artistry of Marcel Marceau and his descendants. But "mime" also draws upon the origins of the word in ancient Greek and Roman shows of simple, often ridiculous imitation. There's a comic aspect to pretending to be another person, a kind of parlor trickery, even if the vehicle is tragedy.

This potentially uncomfortable basis of the art provides a way in for the scorn of Amis and Updike. The American author died in 2009 after a staggeringly prolific career as an honored man of letters. Somewhere he says that theater rests on the weak basis of making scrupulously prepared utterances and actions seem to be spontaneous.

The studied aspect of theater erected an obstacle for Updike, even though he wrote a sort of playable play about the only president to come from the author's home state of Pennsylvania, James Buchanan. To Updike, theater's artificiality was insurmountable and false to life. What characters do and say in a novel or short story takes place in a perpetual present; readers and re-readers make it happen as they proceed through the text. Dialogue and action in a staged play happen within a span of time — a span that's replicated and similarly filled more than once, for audiences, by people assigned to represent events and utterances that pretend to be unpracticed. How can that be anything like life?

The parlor-trick aspect of acting also bothers the Englishman Amis, but mainly as a way to cast into suspicion the whole theatrical legacy. Amis heaps disdain upon a playwright's collaboration with a host of others; the playwright necessarily distances himself from the lives he purports to represent. There are too many others involved. Amis seems to be asking, Where's the artistry in that? "All he has done is finished the dialogue; and, as any novelist knows, compared to the other exertions of fiction the demands of dialogue are negligible."

The essay in which this appears seconds Vladimir Nabokov's own dislike of theater, despite the book under review being a volume of the Russian-American writer's early plays. Amis makes an exception for Shakespeare, but for him it's an exception that proves a dismal rule. In a typically vivid comparison, Amis explains: "The fact that Shakespeare should have been, of all things, a dramatist is one of the great cosmic jokes of all time — as if Mozart had spent his entire career as second wash-board or string-twanger in some Salzburg skiffle troupe."

|

| Voices of the opposition: Martin Amis (above) and John Updike |

It's an amusing but nonsensical analogy, really. But novelists, who are apt to exaggerate the heroic loneliness writing fiction, may be peculiarly susceptible to it. They may play well with others, but working well together is beyond the pale. In his Paris Review interview, Ernest Hemingway said truly that "the most essential gift for a good writer is a built-in shock-proof shit detector," but its mechanics tend to break down when applied to one's own work, as his did. Novels aren't workshopped or devised, and more's the pity, perhaps. (Hemingway came up with a provocative, short closet drama about the Crucifixion, "Today Is Friday.")

Another prolific English novelist, Anthony Burgess, suggests in "Nothing Like the Sun" that Shakespeare yearned to be a lyric poet, but resorted to the theater as a fallback career choice. Hmmm....did we really need more of "The Phoenix and the Turtle" or "The Rape of Lucrece"?

So there you have it: Drama is either a slender reed, always propped up, crafted by committee, and on the brink of wilting and withering in the garden of art (Amis) or it's a scam, since everyone knows that the mimicry is basically contrived deception, at too far a remove from how people actually talk and act (Updike).

To me, though readers' theater is not the ultimate expression of its art form, it may indicate how lifelike working unprepared from a script can be. It largely sidesteps the objections of Amis and Updike. Except for the interaction happening immediately before us, it reduces collaboration to a minimum. It brings to the fore the sprightliness of the text itself, thus coming close to the immediacy of spoken dialogue in real life. Nonetheless, while the perspective of good readers' theater may win this argument, it remains rudimentary to the greater glory of full-fledged theater.

Novelists, I love you, but please tend to your knitting. I'll still often want to drape myself in the finery of theater, in its blend of natural and artificial fabric.

Comments

Post a Comment