On shouting for peace first: suggestions for a social-justice road map in King's 'Letter from a Birmingham Jail'

“No justice!” they shouted. “No peace!”

So ran a line in a Washington Post account of the protest

demonstration in the nation’s capital at the beginning of the month. It was an

odd recasting of the slogan that is usually printed as “No justice, no peace,”

sometimes with one exclamation point at the end.

|

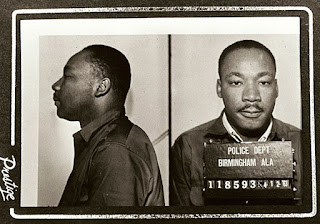

| Mug shots of Dr. King from the jailing that led to his famous letter to white pastors. |

Maybe that’s what we have now: no justice in one silo, no peace in the other. With next to none of either quality, and no interaction between them, we’re stuck.

Of course, the slogan “No justice, no peace” as normally

chanted and felt implies causality: If the protests don’t establish justice,

then there will be no peace. Consequence is necessarily implied, as in the

legendary sign warning customers in Chinese laundries: “No ticket, no laundry.”

A condition for getting a desired result is laid down; if the condition is not

met, you go home without the shirts you had delivered to be cleaned and pressed.

I want to propose that America could do with a period of

reversing the chant, like this: “No peace, no justice.” That’s because it may

be necessary for some kind of authentic social peace to be in place before we

even know collectively what justice might mean as a way out of our current

dilemma.

Thus, any sign of peace in the struggle – as long as it is

not the kind that solidifies an oppressive status quo – should be celebrated.

Without acceptable peace conditions, the hard work of establishing justice is

distorted and perhaps lost in the haze of conflict. We now seem to be too distant from consensus

on peace to negotiate steps toward realizing justice. Thus, there’s a tangle of proposed fixes to

policing that vary from structural reforms through prohibition of certain

techniques (no-knock entry, choke holds, etc.) to “defund the police,” a phrase

that has been relentlessly parsed since it entered common parlance just a few

weeks ago.

Where along this spectrum is justice? We can’t know. Nor can

we know, in order to establish justice, how much renaming of military bases and other institutions is necessary,

how many statues supporting discarded values should be torn down, or how many

black and brown faces need to appear in group portraits of boards of directors. And that’s because we are purporting to know,

from a variety of perspectives, what justice is when we have no common basis

for defining and enacting peace.

Some activists have used Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” as a

foundational text for the current slogan. I believe his remarkable essay better

supports my revision of it. Yet I

readily acknowledge that he saw in April 1963 considerable overlap of the two

concepts, and he privileged the inclusion of justice within a peaceful starting

point that would allow movement away from the conservative talisman of “order”

in the Jim Crow South.

In a long plea for the understanding and support of white

pastors in Birmingham who had paid for the New York Times ad condemning civil-rights

activities led by King in the Alabama city as “unwise and untimely,” the imprisoned

activist sets the justification of the sustained protest in the broadest

possible context, always with nonviolence and a search for common ground at its

core.

For example, right after stating that “injustice anywhere is

a threat to justice everywhere,” which may seem to set down justice as a necessary

condition for peace, King says: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality,

tied in a single garment of destiny.” I submit that enunciating such a value is

central to King’s ministry and his activism.

The common destiny provides the foundation for a peace achieved only

with the acknowledgment of that mutuality. It is what he calls “a positive

peace,” from which “the myth of time” is rejected. This striking phrase alludes

to the Southern moderate’s insistence that justice can only emerge over time.

As King pungently says, too often this means that the counsel of “Wait!”

amounts to “Never!”

Through example as well as sustained tension, King lays out

four basic steps in any nonviolent campaign: “1) Collection of the facts to

determine whether injustices are alive. 2) Negotiation. 3) Self-purification

and 4) Direct action.”

Three out of the four steps are manifestly peaceful. The

fourth one, prepared for by adherence to the first three, can be seen as the

most threatening to the power structure, but it at least makes the needs of

justice explicit. Before direct action is undertaken, the vision has been

honed, and the means to the desired end has been subjected to constant

discipline. “Over the last few years,” King says in his peroration, “I have

consistently preached that nonviolence demands that the means we use must be as

pure as the ends we seek.”

This clarion call for peace as a default position in the

agitation for true equality is not as popular to quote today as “…freedom is

never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed,”

but the latter quotation doesn’t really depart from King’s full description and

justification of the Birmingham campaign in his jail letter. The demand

proceeds from the indelible notion of a positive peace, propounded through

negotiation and steady communication of a positive message.

As a rallying cry, “No peace, no justice” is unlikely to

galvanize well-meaning crowds in the streets.

But as a condition for the progress we so desperately need, “No peace, no justice” ought to be the

thought that fortifies progressives against the extremes that promote rickety,

ill-conceived, conflicted and sometimes dangerous notions of jerrybuilt justice. The edifice of true justice requires the

scaffolding of peace.

Comments

Post a Comment