Posts

Showing posts from July, 2017

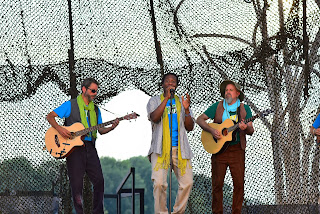

Indianapolis Shakespeare Company, sporting a new name and fine prospects, puts "As You Like It" on at White River State Park

- Get link

- Other Apps

"If music be the food of love, play on," begins a famous comedy of Shakespeare's, not the one the Indianapolis Shakespeare Company (IndyShakes) is presenting this weekend at White River State Park. "Twelfth Night" has the subtitle "What You Will," a hint that the playwright is toying with the same mood of caprice and multivalence more conspicuously signaled by "As You Like It," the company's 2017 production. And the band played on: The songs were peppy, but challenged the action. The first full performance of the show came Friday night, Thursday's having been cut short by a cloudburst near the end of the first act; the run concludes tonight. Nature's capriciousness held off for the actual opening night under sunny skies. Orsino's line about music and love — and the vehicle of food that transports us into a world of ungovernable appetites — came to mind as the primacy of love in "As You Like It" was both enhan

The President Is Getting Stranger: You knew that, but here's a song to sum it up, with the evidence of his Boy Scout Jamboree oration

- Get link

- Other Apps

Sean Imboden's burgeoning big band moves indoors for its second-ever engagement

- Get link

- Other Apps

No cabin fever: Sean Imboden got good results from his big-band outing. Scheduling rehearsals for a newly-formed big band whose members necessarily have day jobs is just one of the threats to a large jazz ensemble's viability. However long it stays together with a stable personnel list, the Sean Imboden Big Band made an exciting indoor debut — and gave cause for celebration — Wednesday night at the Jazz Kitchen. The leader, an Indianapolis native schooled in his specialties at Indiana University and Queens College in New York, guided the 17-piece band (counting the leader's occasional turns on saxophones) in compositions and arrangements he's written over the past several years — plus those of a trumpet-playing friend, Matt Riggen, who also conducted. The band had its first public appearance earlier this summer under damp conditions in Broad Ripple Park. The first Jazz Kitchen set was loaded with promise. The blend took a while to jell, in part because realizing

Hot buttons and tender buttons: 'Human Rites' examines tissue issues (and more) in Phoenix world premiere

- Get link

- Other Apps

Aristotle described it a couple of millennia ago: the point in the drama where everything reverses suddenly. The device makes for a hairpin turn in "Human Rites" as a pitched verbal battle between a black American university dean and a white professor shifts to a drastic new level with the entrance of a third character, a brilliant graduate student from Sierra Leone. Michaela and Alan: Two academics at vigorous cross purposes. Seth Rozin's "Human Rites" needs this peripeteia, as the Greek philosopher described it, giving the example of the worst possible news King Oedipus could get in the tragedy that has made his name and fate immortal. Rozin's long one-act is receiving its world premiere this weekend to conclude Phoenix Theatre' s 2016-17 season. Performances continue weekends through Aug. 13. Seen Friday night on the intimate Basile Stage, the drama benefits from the audience's closeness to the action. With a play so heavily focused on iss

A new kind of magic for 'The Magic Flute' in Cincinnati Opera Summer Festival production

- Get link

- Other Apps

There is a world elsewhere in "Die Zauberflöte," and there always has been. It is not Coriolanus' world of bitter self-exile , but a bright place of earned happiness in which all the sorrows of worthy people are wiped away. The opera, the last work of Wolfgang Mozart's to be staged in his lifetime, adapts readily to an emphasis on show and spectacle as it carries its ethical message to a triumphant conclusion. Cincinnati Opera has done well to bring this particular world elsewhere to regional audiences through Sunday. Many far-flung forces, both creative and technical, came together to create "The Magic Flute" (as it's best-known in Anglophone countries) in the form it's taking this weekend at the Aronoff Center for the Arts in Cincinnati. The production, which originated at the Komische Oper Berlin, has co-production credits from Los Angeles Opera (costumes) and Minnesota Opera (set construction). The creative team was put together by Barrie

Into the discomfort zone: 'Song from the Uproar' muses on a turn-of-the-20th-century Swiss woman's self-exile to Algeria

- Get link

- Other Apps

Isabelle (Abigail Fischer) is swept up in Sufi mysticism in "100 Names for God," a scene in "Song from the Uproar." Cultural consciousness of female self-fulfillment is at a fever pitch nowadays, but it was an extraordinary, fraught experience for our grandmothers and great-grandmothers, exercised only fitfully and at great risk. When put in the context of opera, a brave woman's story pushes back against the legacy of female heroines both vulnerable and victimized, with occasional outbursts of heroism, slanted toward maleness: Beethoven's Fidelio has to be a man for the sake of rescuing a man. Missy Mazzoli and Royce Vavrek have an exceptional tale to tell in examining "the lives and deaths of Isabelle Eberhardt," to quote the subtitle of "Song from the Uproar." The one-act opera opened Monday night in a Cincinnati Opera production in collaboration with concert:nova , a local chamber-music organization. The unusual plurals in th

Without a song: Infusion Baroque visits from Montreal to acquaint Early Music Festival audience with Italian instrumental music

- Get link

- Other Apps

It's more than a ghostly influence — the Italian language that's shot through classical-music lingo — even though just about Infusion Baroque of Montreal opened the festival's final weekend. everyone thinks of the Austro-German repertoire as central to concert life. "Allegro," "andante" — all those tempo and expression directions in the scores — and of course two of the most common types of classical pieces, the sonata and the concerto, fly the Italian flag. Ditto with instrument technology, particularly of strings, that represents the gold standard to this day: Stradivari, Amati, Guarneri. Oh, and the musical scale note names. Where does it end? The prominence of Italian reflects the fact that not only opera, but also instrumental music, owes much of its origin and development to musical ingenuity on the boot-shaped European peninsula. This early, enduring power was reflected in "An Italian Voyage," the program that Infusion Baroque p

"A Wray of Sunshine": The power of the Presidential pardon may be the ace in the hole of the most recent Trump appointee, pending confirmation

- Get link

- Other Apps

Early Music Festival: Henry Purcell, England's greatest composer before the 19th century, viewed from a popular perspective

- Get link

- Other Apps

The clearest indication of what "The People's Purcell" — the program La Nef gave Friday in the Indianapolis Early Music Festival — was all about came with the encore. Michael Slattery: The ingratiating tenor soloist with La Nef in its Purcell program. Not that the Montreal ensemble, featuring the captivating tenor Michael Slattery, hadn't already signaled its approach to the 17th-century English composer in both its music-making and the program note. But "When I am laid in earth," known as Dido's Lament from the opera "Dido and Aeneas," is probably Purcell's greatest hit. Before singing it, Slattery invited the Indiana History Center audience to consider it in the same light as "Memory" from "Cats." Given its familiarity, you could readily note the difference between the stately original lament of the North African queen, abandoned by her lover Aeneas on his way to found Rome, and the La Nef stylization that fol

'Trumptown Faces': Everyone in a Warsaw crowd today had been extremely vetted to favor Trump & Duda

- Get link

- Other Apps

"Sing a Song of Mike Pence (The Path Forward)": Repurposed nursery song suggests how the Veep's discretion may get him what he wants most

- Get link

- Other Apps

First Folio Productions and Catalyst Repertory: 'Richard III' pokes sticks into the hornet's nest of royal succession

- Get link

- Other Apps

So much energy is concentrated in the character of the Duke of Gloucester, scheming to become King Richard III, that the Matt Anderson in a rare moment of calm in the title role of "Richard III" young Shakespeare was hard put to render full-bodied everyone else in the hunchback's orbit, and not just like iron filings around a magnet. It's a credit to a new production by First Folio Productions and Catalyst Repertory that the other roles are vividly filled. They may rant at and lament his cold bravado and be appalled by his ruthlessness. They flail against Richard's ferocious will just to survive. Still, they amount to something in their usually vain struggles. There is something more to them under Glenn Dobbs' direction to make Matt Anderson's excellent portrayal of the title character more than a star turn. But any "Richard III" that really works has to start and end with how the main role is executed. On that score, the new product