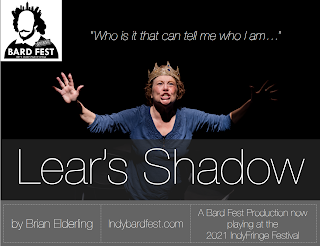

Fringe Festival's second weekend: Vexed and vexatious families and frayed bonds

Many years ago, reviewing theater for the Flint Journal, for several summers I got to zip over to Stratford, Ontario, during opening week of its Shakespeare Festival. By the early '70s, the event had spread its wings to glide through more non-Shakespeare productions. It eventually dropped "Shakespeare" from its name, while continuing to specialize in the Bard of Avon's plays, most of them presented on its sturdy thrust stage. No artfully framed proscenium-arch peep-show presentations for the Stratford Festival ! Speedy aisle entrances and exits and an emphasis on main-action three-dimensionality were embedded in the style. Memorable in this repertoire among the guest stars was the appearance of Peter Ustinov in the title role of "King Lear." An actor of considerable range and subtlety, Ustinov had a genius for comedy. So his casting in the leading role of Shakespeare's most searing tragedy stirred both eagerness and anxiety. The role is regarded as ...