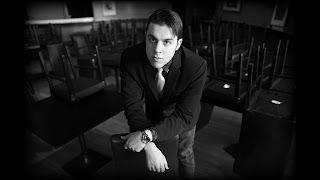

American Pianists Awards' Premiere Series opens with turbulent, surprising Esteban Castro

A week ago, the cameo self-portraits of five young pianists were topped by the contribution of Esteban Esteban Castro, 20, channels both Prokofiev and James P. Johnson. Castro. The free concert in the Madame Walker Theater Sept. 18 yielded the most promising performance in the work of the youngest contestant, as the American Pianists Association presented its five finalists for the Cole Porter Fellowship in Jazz. A New Jerseyite, now a New Yorker studying at the Juilliard School, and with a firm grounding in classical music, Castro treated his trio mates well inaugurating the Premiere Series of trio sets Saturday night. Yet he chose to devote a large proportion of his 70-minute second set at the Jazz Kitchen to expansive, unaccompanied playing. Often the trio would rejoin him by simply sliding into place, as if the three had been working together for a long time. That effect can be credited in large part to the skillful collegiality of bassist Nick Tucker and drummer Kenny Phel...