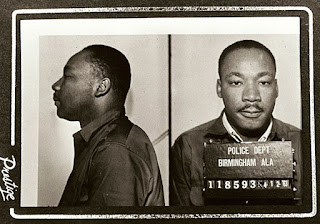

“No justice!” they shouted. “No peace!” So ran a line in a Washington Post account of the protest demonstration in the nation’s capital at the beginning of the month. It was an odd recasting of the slogan that is usually printed as “No justice, no peace,” sometimes with one exclamation point at the end. Mug shots of Dr. King from the jailing that led to his famous letter to white pastors. The Post version may have inadvertently evoked the kind of stalemate that America’s stubborn racial struggles have reached. If you separate the phrases by more than a comma, as the Post did, you place them as neighboring pillars with no implied link between them. Maybe that’s what we have now: no justice in one silo, no peace in the other. With next to none of either quality, and no interaction between them, we’re stuck. Of course, the slogan “No justice, no peace” as normally chanted and felt implies causality: If the protests don’t establish justice, then there will be no peace. ...