Hoosier violinist is vital to success of 'Within Us' by Chuck Owen and the Jazz Surge

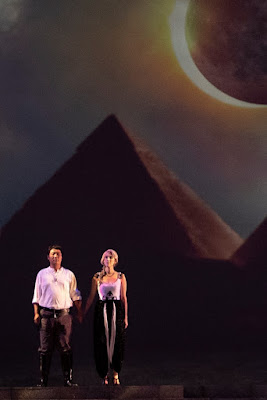

In addition to the well-crafted band arrangements of "Within Us," the silver-anniversary recording ( Mama Records ) by Chuck Owen and the Jazz Surge is welcome for the generous spotlight shone upon Sara Caswell, a violinist with a prominent Indiana University pedigree, trained early in classical music before she went through IU's renowned jazz curriculum created by David Baker. Sara Caswell makes major contributions. She gets several solo outings in the course of the eight pieces, some of them setting the stage for Owen's extensive ensemble thoughts. She introduces the deliberations of "Trail of the Ancients" with trenchant musings, and when a regular tempo is established and guitarist LaRue Nikelson sets a pattern, she supplements his recurring contributions in deft phrase endings. Later, Caswell soars, and the tasty voicings for the ensemble make a perfect setting. After a guitar cadenza, there are exchanges between the two soloists to put a cap on a me