For "Sonic Creed," Stefon Harris puts together a mellow program featuring his regular band Blackout

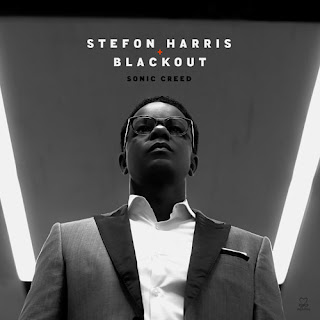

The vibraphonist Stefon Harris has helped extend the historical roster of major jazz stylists on mallet percussion. Cover art: The severe visual presentation seems at odds with the music inside. This year he has released "Sonic Creed" ( Motema ) with his band Blackout, and is touring on the strength of the album. He will appear at the Purdue Jazz Festival on Jan. 18; and, as a solo player and working with students, at Butler University April 3 and 4 "Sonic Creed" represents him in mid-career (he's 45) as a receptive bandleader with a way of showcasing multiple lines, many of them rhythmic, simultaneously — but without clutter. The catchy Bobby Timmons/Oscar Brown Jr. song "Dat Dere," opens this disc amiably but with distinction. In the front line, Harris and saxophonist Casey Benjamin display a compatibility that runs throughout the program. The two don't shy away from melodic invention, they are assertive without aggressiveness, and they