Playing well with others: American Pianists Awards puts finalists in collaboration

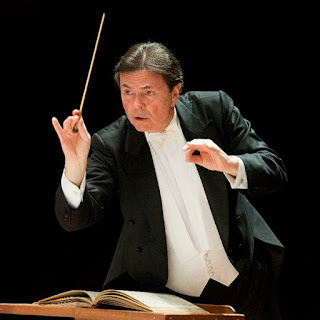

The chamber-music and concerto phases of the 2021 American Pianists Awards have necessarily been squeezed into one concert each, meaning that much of the repertoire was trimmed down to a movement or two per pianist. The second concert presented the finalists working with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Gerard Schwarz; on Friday each had been joined by the excellent Dover String Quartet at the Indiana History Center.

The competitive aspect of the quadrennial classical division (every other two years is devoted to jazz) of these well-heeled contests has thus been given a focus with pluses and minuses attached. A concert artist, especially in collaboration, develops a concept of a chosen piece that brings out his or her personality across the spectrum of a composer's unified creation. Nonetheless, a movement of significant length is also a unit of creative and interpretive achievement, and listeners (including the jury) don't have to divide their impressions over two or more concerts per genre, as was the APA's pre-pandemic custom.

So, except for two compact works in concerto style, the last two nights concentrated the attention in ways

|

| Gerard Schwarz was concertos' guest conductor |

that asked us to forget about movements that were not played. On Saturday at Hilbert Circle Theatre, we heard the first movements of three Beethoven concertos, plus two complete works that fit within the roughly 20-minute portion assigned to each participant: Cesar Franck's "Symphonic Variations" and Franz Liszt's Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major.

Taking the complete pieces first, Kenny Broberg followed up on the unity and firm ensemble sense he had displayed in the first movement of Brahms' Piano Quintet in F minor with a scintillating account of the Franck, a work that mounts through richly lyrical treatments of its theme onto the kind of Second Empire thrust Franck was capable of in the concluding Allegro non troppo, supported incandescently by Schwarz and the ISO.

Inevitably, the mind's ear went back to a Franck composition more explicitly indicative of the composer's career as an organist, the first movement of the Piano Quintet in F minor, which Michael Davidman played with the Dover. I had not heard Davidman's solo recital for the competition, so was enthralled by his playing for the first time Friday.

I don't know how much today's burgeoning pianists and singers listen to their recorded legacies, but Davidman certainly sounded familiar with the French tradition of piano-playing, exemplified by Alfred Cortot, Marguerite Long, and Robert Casadesus. Trying not to make too much of comparing present-day concerts with historic recordings, I am yielding to that temptation here: the anonymous liner-note annotator to my LP of the Thibaud-Casals-Cortot performance of Mendelssohn's Piano Trio in D minor concisely nails the French pianist's special qualities: "intense sensitivity and ample yet varied tone."

The delicate force of Davidman answering phrases to his string colleagues' "questions" as the Franck got under way was captivating. His accents, when called for, were impressive, ringing out without overemphasis. The facility in rapid passagework was unstinting and always under control, yet with the flair of spontaneity. I was looking forward to appreciating Davidman's own "intense sensitivity and ample yet varied tone" in the Liszt concerto, and I was not disappointed.

|

| Michael Davidman shares wide performance experience with his competition colleagues. |

The evenness of touch sparkled, but special emphases were not ignored. There's a left-hand line as the second-movement melody unfolds that, in this performance, had an uncanny richness of tone, as if a master baritone were singing it. The excitement of the "Allegro Marziale animato" was introduced with masterly suspense, and the thrills of that finale seemed truly earned by the "intense sensitivity" the pianist had displayed previously. This was not adventitious excitement applied out of nowhere; it had been present, thanks to Davidman's acuity and interpretive elan, from the start. All told, and given the simpatico accompaniment and the orchestration's brilliant variety, this was one of the best concerto performances I've heard in recent years.

No, I'm not going to advocate for Davidman as rightful winner of the Christel DeHaan Classical Fellowship to be announced this afternoon. I'm a little wary of musical competitions, though this one is well-run and, as a music journalist, I've been appreciative of their publicity value: they attract audiences, they attract money. May the excellence of these five young pianists in this showcase usher in significant careers all around; they deserve to be heard.

Of the rest of Saturday's program, I'll admit to a long-standing regard for the Beethoven Fourth as my favorite. Dominic Cheli's performance of the G Major's first movement opened with a thorough gentleness that was matched by the orchestra's response. I was impressed by his shapely legato touch and his apparent acknowledgment that this work foreshadows the romantic century, especially in the solo concerto form. Cheli's cadenza seemed to encompass all sides of the music, with some detectable, idiomatic enlargement of one of Beethoven's versions.

Beethoven's C minor concerto, the Third, is suffused with the earnestness of middle Beethoven. It might not have been to all tastes that Mackenzie Melemed, with his spidery touch and nimbleness of phrasing, brought out the lightness of the solo writing, loading most of seriousness onto the cadenza. I found this well-founded, mood-lifting approach a relief, partly because the Third is my next-to-least favorite of Beethoven's mighty five.

Yes, the "Emperor" is the beast in the room. It received a respectful, appropriately insightful account of the solo role by Sahun Sam Hong. Still, this masterpiece rubs me the wrong way, partly because its greatness absorbs all interpreters and even beats down admiring listeners. Individuality of expression from the piano and the robustness characteristic of the orchestra accompaniment add up to an excruciatingly detailed landscape painting.

|

| Tolstoy, like Beethoven, painted on huge canvas. |

Putting one's concerto all into this one mighty movement subsumes just about every interpretation. It's as if the philosophical and historical position of the E-flat concerto both props up the individual and sets him firmly into a huge context that's larger than any one pianist — or any one of us, frankly. That makes this work worthy of its nickname, but it's not an ideal contest piece, despite Hong's evident commitment to it.

The "Emperor" could be regarded as the "War and Peace" of piano concertos. It doesn't matter whether you're Napoleon (central to the generation of both works) or Prince Vasily or a foot soldier. As Tolstoy implied, a remote, all-powerful god is in charge. In this concerto, Beethoven is that controlling yet oddly remote deity. We are accustomed to looking up to him in such a position. So, in the best sense of reviving the concert scene, exposure to three of his concerto first movements in the contest's final round is not regrettable, despite my imperial reservations.

Comments

Post a Comment