IU's season-opening production of 'The Magic Flute' brings forward Mozart's music with some dramatic shifts

|

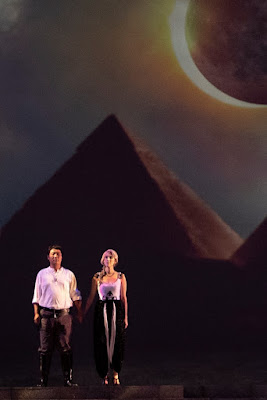

| Tamino and Pamina reach trial's final stage. |

To begin with, Monostatos would need his comic villainy whitewashed. It was easy to assume this in advance of attending "The Magic Flute" in Indiana University's Jacobs School of Music production, which began a two-weekend run Friday night.

And so it was. The reigning Priest of the Sun's bad hire could no longer whine about his blackness or his ugliness, as the libretto to Mozart's masterpiece has it. In an era where it is controversial to darken the features of a white tenor singing Otello, there would be no way to adhere to the original in that respect.

But more central to the story is the way it upholds patriarchy, albeit of an enlightened and ethical kind. There are hints of IU's different direction well before the arch-villainess Queen of the Night and her adherents are symbolically embraced in the realm of her nemesis, Sarastro. That's the staged equality of this production's final scene, capping director Michael Shell's up-to-the-minute interpretation.

In 2021, clearly enlightenment needs to presume that higher levels of humanity are accessible to everyone. Even the undeniable musical contrast between the bass Sarastro, who sings the only music that could be imagined to come from the mouth of God (according to George Bernard Shaw), and the dazzling, vengeful coloratura flights of the Queen can't be allowed to resulting in her utter vanquishing at the final curtain. Resolution must be complete and supportive of a truly enlightened outlook, as I read Shell's version. Men and women need each other on equal terms — a swerve away from the opera's message that they need each other under the guidance of men.

|

| 'That woman': The Queen of the Night in her element |

Confirmed by the surtitles, a priest's early warning to Tamino against submitting to the wiles of women needed to be pinpointed as a demand to resist "that woman," the Queen of the Night. The production goes far to remove gender bias. In one of the choruses, the white-robed women protest against their exclusion with waving fists. The choral singing was splendid Friday night, by the way.

Fortunately, the vital thread on which the contemporary interpretation hangs is the authentic elevation of Pamina, the Queen's daughter, to worthy partnership with the prince Tamino as he seeks admission into Sarastro's order, motivated by his love for Pamina. That's in the original libretto, part of impresario Emanuel Schikaneder's chock-a-block mixture of high-mindedness and buffoonery. The character is clearly special, and Tamino couldn't have come through his trials without her devotion; but in this production, she is also an avatar of powerful sisterhood.

Not surprisingly, then, this Sarastro combines nobility with — in the spoken English dialogue — an occasional offhandedness. When one of the priests questions why the amiable, loutish bird-catcher Pagageno is being allowed to undergo trials along with the idealistic Tamino, Sarastro says that's just for fun. And why not? The pair are just accidental companions, and life's variegated way of throwing people together is a major driver of the "Flute" plot. Hints of quasi-divine capriciousness are not out of place, as Jehovah illustrates time and again in the Old Testament.

The cast I saw set Yuntong Han and Ian Rucker as the unlikely partners-in-hazing to which Sarastro's order has assigned them. Stress at my late arrival caused by travel difficulties from Indianapolis was relieved by Han's smooth, ardent performance of "Dies Bildness ist bezaubernd schön," the first music I was able to hear after hasty seating at the Musical Arts Center. (Han would prove impressive both vocally and dramatically in each subsequent appearance.)

I'm sorry I missed Papageno's zesty song of self-introduction, "Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja," which I suppose must have been captivating, based on how well Rucker threw himself into the role. Of course, not hearing the expansive, deftly foreshadowing overture was also regrettable. If Arthur Fagen's sensitive handling of the orchestra subsequently was any indication, it was a kaleidoscopic delight as an introduction to the rites and revels.

|

| Papageno and Pamina compare notes. |

Rucker's portrayal included the most of several tweakings of the spoken dialogue toward modern colloquialisms. The Shickaneder spirit ruled in such revisions; Mozart's friend and collaborator always had his finger on the popular pulse. The theatrical Singspiel tradition that the composer enhanced when working with his native German meant he never disdained lowbrow stuff. Some of his letters are notoriously smutty. One can only write one great Requiem, after all, and Mozart's efforts toward a comedy embracing his Masonic values had to be interrupted by that mysterious, sacred commission. To the dying composer, one task was probably a welcome relief from the other.

Visually, the production fills the capacious stage with authority; there's no doubt about the solidity of the Sarastronian infrastructure. Temple and vaulted hallway vistas are imposing along the back. Of the special effects, only the attraction of beasts and birds to Tamino's flute seemed wispy, as the projected birds flitting about looked more like wind-blown leaves. (Lighting, set and projection designs were the work of Mark F. Smith and Ken Phillips.)

In contrast, the Queen of the Night is treated to star-flaming dazzle, accompanied by a brilliant full moon, for her iconic aria in the second act. Elise Hurwitz handled its demands capably, and carried herself with authority in the spoken dialogue as well. When the Queen's realm collapses, the lighting design remarkably represents the impact of its downfall. If she had to suffer such a spectacular defeat, she probably deserved the salvation that this production extends to her at the end.

|

| IU's Three Spirits: Always good for a bit of intrusive wisdom |

There was a "steampunk" or graphic-novel flamboyance about some of the costuming. It vividly depicted Monostatos and his creepy, skittering henchmen, as well as the retro-urchin look of the original's Three Boys. They supply warnings and advice to the three adventurers, move about on a unique wagon cycle, and represent a kind of streetwise spirituality, delightfully sung by three sopranos and thus rechristened Three Spirits. More substantial trio work for sopranos (of which the Jacobs School has long had dozens at a time) was given well-blended assertiveness by Giuliana Bozza, Jessica Bittner, and Catarine Hancock as the Three Ladies.

Jenna Kreider's Pamina suited Shell's concept of a woman sure of her place in Tamino's progress, but her voice was a little less suited to project vulnerability and self-doubt. "Ach, ich fűhl's," the tenderest lament, had a steely core to it, which could be arguably defended as representative of this crucial character as she works her way out of victimhood with both natural and supernatural help.

The height difference between Rucker and the Papagena he is cast with, Adriana N. Torres Diaz, is exploited amusingly in their reunion duet, which earned the opening night's biggest ovation until the final one. Another worthwhile episode of hilarity was the coordinated dancing of Monostatos and his men once the glockenspiel Pagageno carries cranks into operation and defuses their menace into a helplessly silly departure.

How seriously we are to take Sarastro's priests and hirelings, given that their boss is only intermittently lofty in demeanor, remained a question to me. As delivered, some of their spoken dialogue seemed sarcastic, some merely earnest. The Speaker (Edmund Brown) was rather neutral in his brief sung conversation with Tamino. The two Armored Men had their slight but aptly severe roles sung with coordinated fervor by Cody Boling and Drew Comer.

Here and there, slight coordination problems between stage and pit popped up, but on the whole action and music were well-integrated. "The Magic Flute" is in an odd way perpetually avant-garde, despite its Singspiel heritage. There's nothing like it in today's core opera repertoire, and IU's production really believes in "The Magic Flute"'s oddities as well as its majesty. It delivers an interpretation duly adjusted to modern tastes but respectful of the work's permanent brilliance as well. Two performances remain next weekend; the opening-night cast returns Saturday, with the September 18 cast reappearing Friday.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete