At Early Music Festival, the solo song: what love has to do with it

|

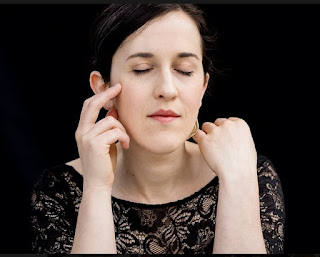

| Soprano Arwen Myers, perhaps dreaming of love |

The lively program note to the recital Friday night by Arwen Myers and John Lenti sketched as wide a series of attitudes to romantic love in the early Baroque as would be constituted later by the American popular song. The topic of winning and losing in affairs of the heart never grows dull.

"Listen Up, Lovers!" as a title for a concert introducing a voice-centered weekend in the Indianapolis Early Music Festival caught the durably imperative note in early 18th-century art songs: One addresses love as something one deserves, despite its disappointments. Musically, the repertoire rests on the towering achievements in Renaissance song literature, including the polyphonic supremacy of the madrigal in England and Italy.

The elaborated sentiments take love with enduring seriousness, even when the mood is flirtatious. The duplicities of love expressed verbally encourage cultivation of visual cues: "Love, that fickle little god, teaches us that wordless language," reads the translation to the first French song presented at the Indiana History Center Friday, after an English set focused on Henry Lawes.

But exchanging looks of devotion cannot get around love's

contradictions, which may require words like these, in a song by Barbara Strozzi: "I have

pleasure only in weeping, / I nourish myself only with tears. / Grief is

my delight / and groans are my joys." Thus reads part of the English

translation of

"L'eraclito amoroso," one of the duo's triumphs in this

concert: "Udite, amanti," the song insists at the outset, providing Myers and Lenti

with the program's title.

The soprano and lutenist (who here used baroque guitar and theorbo, a double-necked bass lute) surveyed a variety of English, French and Italian song. Oxymorons in the texts have prompted composers to oppose meanings cheek by jowl, displaying their adroitness. The performers seemed always alert to bringing forward contradictions in both vocal and instrumental parts. What the voice declared, the plucked instrument confirmed. The musical empathy was just as firmly presented: in Claudio Monteverdi's "Si dolce e il tormento," the rhythmic steadiness and the accents that support the lines were evenly distributed between the musicians.

|

| John Lenti and theorbo |

The most extended maintenance of a complex mood came with Tarquinio Merula's "Hor ch'e'l tempo di dormire," less a song than an operatic scena. It takes the frame of a lullaby, Mary to the infant Jesus, and becomes a prophetic vision of his Passion and death. The foreshadowing was intensified by vigorous strumming of the guitar. Eventually, the lullaby mood returns, and the song's restful conclusion found the duo at its sensitive best. The song's apotheosis of maternal love added a transcendent perspective to a program otherwise giving prismatic display to secular love, whose nobility is always open to question. There's the ache of devotion, but also what Lorenz Hart called "the conversation with the flying plates."

Comments

Post a Comment