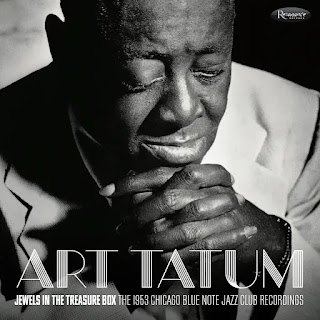

Venerated pianist at a great jazz club. Resonance erects monument to the uniqueness of Art Tatum

A midcentury fixture in Chicago's Loop, the Blue Note played host to a variety of the era's brightest stars under the watchful, welcoming eye of Frank Holzfeind, who founded the club in 1947. Now, by arrangement with the proprietor's family and with cooperation from the Art Tatum Estate, comes a three-disc set of Tatum trio performances from August 1953.

Resonance Records last month released "Jewels in the Treasure Box," a package with the label's usual elan of verbal and visual support in the accompanying booklet. The classiness rests on a firm foundation of worthy recordings, previously unreleased and brought to light with the tireless dedication of Zev Feldman.

Tatum is the genial, relaxed voice introducing the tunes, reflecting his comfort at the jazz club — an impression he shared with many other great jazz figures who appeared there, including Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington. The pianist's rapport with his sidemen, guitarist Everett Barksdale and bassist Slam Stewart, is consistent over a program based on the Great American Songbook.

Nearly blind yet extraordinarily conversant with his repertoire and all its decorative possibilities, Tatum had a few quirky favorites outside the G.A.S. terrain. Here there is a solo version of Dvorak's Humoresque, for example, treated with apt fancifulness. In common with other unaccompanied performances long available without mates on the bandstand, in this one Tatum felt free to vary tempo and wander into cadenza episodes that were clearly spontaneous yet rich in controlled inspiration. In the August 16 session, perhaps this package's most pristine, he follows "Humoresque" with Cole Porter's "Begin the Beguine." This version is flamboyant at every turn, yet also grounded in the stride piano style that informed his youth.

Of the predominant trio performances here, there are many standouts. "Just One of Those Things," a song beloved of jazzmen for its invitation to cut loose, gets a hearty response from the group. Barksdale's solo is just about as amazing as Tatum's, and Stewart applies his wit and patented solo style — bowed and vocalized lines in unison — to his turn in the spotlight. The pianist could paraphrase a melody out to the edge of "playing the changes" then come back to the tune, still taking it for a succession of flights. His "fills" between phrases are brief but telling glimpses of the virtuosity he always had in reserve. They provoke the kind of wonder a magician generates when he conjures white doves flying out of a top hat.

"Just One" is succeeded by an example of Tatum and his men settling into an easy stroll: you are eager to drift along with the trio inviting you to "Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams." That tempo was an old favorite of the pianist. He unfolds "Where or When" with the pondering pace of a cowboy ballad. He liked to have plenty of room between phrases for filigree of such expanse and precision that everyone in jazz knew had no equal. The evenness of touch had the sheen one expects of classical pianists, and the spontaneity tended toward the marvelous.

It's no wonder that Vladimir Horowitz paid a visit to a Tatum gig and marveled over how he played "Tea for Two." The great Russian asked the great American how long it had taken him to learn "Tea for Two." "I just made it up," Tatum replied. Harold Schonberg reports in his biography that Horowitz went home and worked up his own arrangement of "Tea for Two," which he played at parties.

Stewart's versatility is an amazing bonus in these performances. His pizzicato accompanying is up to the standard that Tatum represents, and he is then always ready to pick up the bow and layer his humming/scatting voice on top of the bowed line in parallel. Slam's typical ebullience can be readily appreciated by Hoosiers in the trio's performance of "Indiana," an interpretation that's fast, jumpy, and compact.

It has to be said that the audience noise on Disc 3, especially in the last session for which Holzfeind's tapes exist (August 28) is a little intrusive. Nonetheless, it's a matter of social life basically connecting with the music, and never seeming to ignore it, fortunately. Tatum even compliments the audience at one point on its attentiveness. The Blue Note's patrons clearly knew they were in the presence of a remarkable interpreter of tunes everybody used to know. Now fans of new recordings can get to know even more of the genius Tatum had to apply to every song he touched.

Comments

Post a Comment